Goodness! It was a terrific reading year. Here’s a list of our faves, in no particular order:

Children's Picturebooks: The Art of Visual Storytelling by Martin Salisbury

This book is a bible for anyone interested in the world of books for children. It is such a departure from the blurbs and previews that flood kid-lit insta and review publications that are rightfully focusing on current releases. It roots the history of the medium with hard to come by, out-of-print titles that visually stun: these are objects worthy of their own study as art and storytelling vehicles. Follow the dizzying thread of recommended titles of wordless picture books, postmodern picture books, and (even) books about picture books.

It was here where I discovered my absolute favorite book maker...

Beatrice Alemagna

(Buy her books for you, not your kids. Perhaps share them with your kids, if they are nice.) The Wonderful Fluffy Little Squishy was a game changer for me: oh, you can make a book like this. A Lion in Paris is also very good, especially for Francophiles out there, but Fluffy Little Squishy transcends the medium itself. Seriously, this is brilliant storytelling wrapped up in illustration and verse.

A Newspaper for Kids

The New York Times released a children’s section this year and recently announced that it will be a regular (monthly) thing. Yay for print!

Here Wee Read

Here Wee Read is a fantastic resource that I learned about in 2017; it’s here where I discovered:

Let’s Talk About Race

This picture book was a gift for my two-year-old for Christmas this year, although my five-year-old was much more interested in listening along:

“Why would some people say their race is better than another?

Because they feel bad about themselves.

Because they are afraid.

Because.”

And:

“Those who say

‘MY RACE IS BETTER THAN YOUR RACE’

are telling a tory that is not true."

How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer by Sarah Bakewell

This one is a bit of a cheat — I didn't finish it in 2017.

Bakewell's biography of Montaigne is heavily researched but its delivery isn't dry or dense; instead she refocuses the story of his life through a lens of “how to live” — be born, read books, etc. It’s a clever gimmick that does not fall apart in execution. We meet Montaigne, an upper class boy sent to live with a working class wet nurse for his first year of life. Upon return to his biological family, he was saturated in a humanist education that included a six-year isolation of sorts as Montaigne was raised with Latin as his native language. (His own parents didn’t know the language so he communicated solely with a tutor.)

Like Ron Chernow or Janet Malcolm or Caroline Moorehead or Hermione Lee, it almost doesn’t matter who our subject is: Sarah Bakewell is one of those biographers who elevate the life stories of, yes, remarkable individuals, but in such a way that centers you on the universality of the human experience itself.

Jabari Jumps

Jabari is a boy who's ready to jump off the high dive! But once he sees the view from the top, he has second thoughts. His father listens, validates, and gives Jabari the choice to try again. It’s another version of How to Live; but for Jabari's family, love would be the one-word answer to this question. (Of course, the two father figures — Montaigne’s and Jabari’s, couldn’t be any different.) The illustrations are fresh and modern and minimalist; the story surfaces almost two-dimensionally in that flattened sort of way swimmers appear under a pool’s surface.

Ghosts and El Deafo

There was a major graphic novel theme in our house this year. No surprise that I will project my love of this genre on my own children — I have a huge soft spot for indie comics from the aughts like Craig Thompson and Gabrielle Bell and Chris Ware (played to a soundtrack of Modest Mouse, probably).

Both of these titles share another commonality, too — they center on characters with disabilities. In Ghosts, Catrina's sister Maya is suffering from cystic fibrosis. The family moves to the pacific northwest, a place where the air is easier on her breathing. The transition from Southern California is a tough one for Cat who is all of the things a sister is — at once protective of and annoyed by her younger sibling. Her sister’s disease complicates matters of course and in the end the older sister comes to terms with her guilt and resentment for her sister’s illness. (I read this with my kindergartener but glossed over parts that were too heavy.)

El Deafo is such a sweet story and parents will love the references to growing up in the 80s. Cece loses her hearing after a childhood illness and traverses school, friendships, and insensitive gym teachers as a person living with deafness. My daughter and I talked about what it might feel like to be different — a sentiment that everyone can relate to on some level, especially school age kids who are so aware of preferences and physical differences. It is ultimately a happy story; the neighborhood and school kids embrace Cece (despite the outliers who yell loudly at her or treat her as though she is fragile). We loved this one.

We're All Wonders

We’re all Wonders is the picture book spin-off of Wonders by R.J. Palacio. Auggie has an extraordinary face but all he wants is to feel connected and to belong. It's a book that has an inspired an entire movement, too: Choose Kind.

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This tiny book emerged out of Adichie's 2012 TED talk and was published a couple of years later. It's meant for adults, but for those of you with children coming of age, I highly recommend this book as a starting place for a discussion on what it means to be a feminist and why it is more important now than ever that we center feminism. The book is short, accessible, and hits the nerve of sexual politics in 2017 with sweeping statements such as: "[Part of the problem is] that many men do not actively think about gender or notice gender." Instead, Adichie calls on men to speak out and address the micro-aggressions that women face in their daily lives.

And this: "Some people will say, 'Well, poor men also have a hard time.' And they do. But that is not what this conversation is about. Gender and class are different. Poor men still have the privileges of being men, even if they do not have the privileges of being wealthy."

When a person questions your claim to your identity as a woman ("Why does it have to be you as a woman? Why not you as a human being?"), Adichie states simply: "This type of question is a way of silencing a person's specific experiences."

On another note (with regard to usability and design), I adore the size of this book. It fits in the palm of your hands like a portable Book of Hours for the modern man and woman.

HiLo

HiLo — yes, another comic! — is slick fun. He’s a robot alien who falls from the sky and befriends D.J. and Gina. D.J.’s over scheduled, highly successful, type-A family is written for laughs from us parents; but jokes abound for the entire family’s amusement:

Knock Knock

Who’s There?

Interrupting cow.

Interrupting cow wh—

MOOO!

We devoured this three-part series over a period of two weeks; my five-year-old who can’t yet read spends a fair amount of quiet time looking at this book. I'm noticing that comics are a great way to get young children "reading"— she sees the words as part of a speech or thought bubble and sounds out all of those comic sounds like WHEEEEEE and ZZZZIP and BLURP. She is dying to know what this person or that person is saying and it’s an organic way of following her lead to get her to sound out words that she wants to read.

The Rights of the Reader

Speaking of reading. The Rights of the Reader, you guys. I have talked about this book a couple of times this year: here and here. It's one of those books that I wish every parent could get their hands on. Go get this. And in the meantime, here’s your bill of rights:

The Rights of the Reader

The right not to read.

The right to skip.

The right not to finish a book.

The right to read it again.

The right to read anything.

The right to mistake a book for real life.

The right to read anywhere.

The right to dip in.

The right to read out loud.

The right to be quiet.

The next two titles are recommendations from Heidi Fiedler, a writer and editor with a fun Insta feed.

The Art of Slow Writing

I slow-read The Art of Slow Writing through the slow, slow summer when parenting eclipsed any possibility of a committed creative practice. Louise DeSalvo’s advice is rather simple: focus on process versus product. Do the work, bird by bird. Heck, enjoy the work. Acknowledge that editing your manuscript for the twelfth time is as essential as getting out that first draft. It’s all writing. And this: "Should I write today? Take a weekend off? Work in the morning or afternoon? Am I using being sick as an excuse to not write? ... How did I I become a writer who's comfortable making scores is complicated choices each day of my writing life? I simply decided to practice deciding. ... In writing, it doesn't matter what you choose to do, it only matters that you choose to do something."

Making a Literary Life

Making a Literary Life is that type of book that makes you want to befriend its author. Carolyn See self-describes as decidedly not Northeastern or a New Yorker; nor is she a male Writer with a capital W. But she’s made it — a literary life, that is. Some of her processes are seemingly obvious, but as someone "in it," it's helpful to understand the path one takes to writing a book: pitch some freelance articles. Then, use those writing clips to attach to your manuscript or proposal to find an agent.

One of her key strategies for the rest of the world — you know, those of us who don’t live in Manhattan or know four literary agents — is to send these delightful little notes in the mail on real, beautiful stationery to real people who are making a literary life themselves (and don’t have a clue as to who you are). There are rules to this analog, darling idea, of course: for starters, don’t ask for anything. Compliment their work. Keep it simple. You’re sprinkling glitter in the world, after all.

Her point is basically this: you, too, can have this career. If you really want it, that is.

Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls

Keeping on the topic of rad ladies, I picked up a copy of Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls this year. Partly to understand the voice and rhythm of middle grade non-fiction writing and also because of the two extremely talented creatives and entrepreneurs at the helm of the Rebel Girl biz: writers Elena Favilli and Francesca Cavallo. The anthology format makes it easy to share these short glimpses of remarkable women with your boys and girls, between books or at snack time.

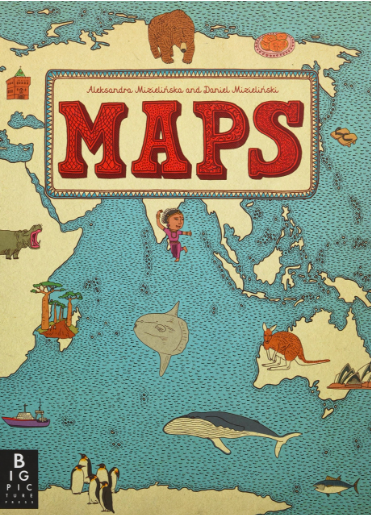

Maps

Our six-year old neighbor J (who introduced us to HiLo) always wanders over to this illustrated atlas and spends some time looking at it whenever he’s at our house. (I had hoped my own kid would do the same. Not yet.) But is so much to look at in these illustrations! — food, customs, dress, pastimes for the 50+ countries that are illustrated. I love taking it out when we talk about other countries or places that our family members are traveling.

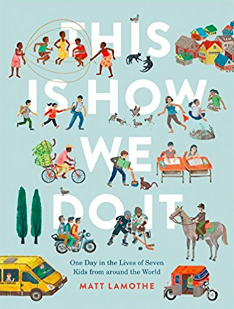

This is How We Do It and Dear Primo

Perhaps it’s a knee-jerk response to our current administration's disastrous plans for a DACA repeal, or their anti-American stance on immigration, but I am trying in my small way to share stories of people who don’t look like us or live in places that aren’t like where we live. This is How We Do It is a graphical feat that resonates with the librarian cataloguer in me: seven children (from Peru, Uganda, Iran, Russia, India, Italy, and Japan) share bits of their daily life with each page centering on a meal, a household chore, a recreational activity, or a living arrangement.

Dear Primo does this in a different way — two boys, a New Yorker and his cousin from Mexico swap letters, pen-pal style to discuss the everyday ordinariness of shopping with mom or playing with friends. It's a simple demonstration to children that the surface stuff might look different, but our commonalities — like the very experience of childhood itself— runs deep.

I loved reading with (and without) my family this year. It was the first full year of keeping up with my Commonplace Book. With social media breaks built-in at least every few months, I did manage more books than the previous year. (When I realized the amount of books I wasn't reading in place of the hours spent scrolling political Twitter I knew I had to readjust and delete the apps on my phone.) Here's to another year of even more reading (and writing) in 2018!